Higher Power

Toronto architect Siamak Hariri ascends to architectural greatness

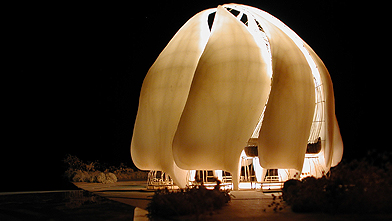

Nights of the round temple: An architectural rendering of the planned Baha'i temple outside Santiago, Chile, as conceived by Canadian architect Siamak Hariri. Courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects.

This week, Toronto fabricators Soheil Mosun Ltd. started building the massive structure that will support the curved walls of a temple soon to be built near Santiago, Chile. The firm was retained by local architect Siamak Hariri to start transforming his designs for the South American headquarters of the Baha'i faith into an actual building.

The design has critics reaching for their most outlandish metaphors. They have compared it, by turns, to a soap bubble, a jellyfish, a lantern, an egg and, most swooning of all, "an enterable droplet of light." The Baha'i House of Worship is exponentially more ambitious than anything Hariri has attempted before. In size, scale and shape, the temple represents a departure for Hariri, while still furthering the lifelong project of this son of refugees: to imbue his buildings with a sense of sanctuary, a retreat from history's hurly-burly. It's a big moment for Hariri: the temple puts the Canadian architect in the international big leagues.

During a recent interview in a Toronto conference room filled with architectural models, Hariri's attire is almost glibly fashionable: his Chelsea boots shine beneath flared slacks; his curly hair is reined in by just the right amount of product; and his puppy-dog eyes are hardened by glasses with angular frames. His patter is practised; he seems as sleek and self-satisfied as a pedigreed cat. But he talks sense about his work, eschewing the gobbledygook so common among the leaders of his profession. Using his laptop to show photos and illustrations of his greatest hits, Hariri mentions one simple idea behind each project, and then describes the technical and design choices he made to meet the client's demands.

Hariri Pontarini Architects, the firm he co-founded with David Pontarini, has grown in the last decade from four to 20 architects, moving from projects valued at several million to one priced at nearly $150 million. Commissions for major buildings have come in from across Canada and, now, from as far afield as England, Germany, Indonesia, the Philippines and Switzerland.

The firm's first major commission was Robertson House, a women's shelter in downtown Toronto completed in 1998. The $4.2-million project — his most literal building-cum-sanctuary — owes much to the influence of Jane Jacobs. The firm combined two Victorian rowhouses, gutting them on the inside while retaining their familiar, street-friendly façades. Before Jacobs's influential book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, there was no honour to be had in preserving and cobbling together a building from old and new parts. You razed what was there and started from scratch, building big and self-contained projects and ignoring the effects on the street and neighbours. Hariri updated a Carnegie-funded library in Barrie, Ont., in a similar fashion, adding a respectful annex (price tag: $5.9 million) to house the McLaren Art Centre.

Architect Siamak Hariri. Courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects.

Like almost every subsequent Hariri building, Robertson House features a secluded courtyard. Even a pair of skyscrapers Hariri has proposed for Halifax have a courtyard garden wedged between them. Usually filled with plants and water, these courtyards promote the sense of serenity, of retreat, common to Hariri's creations.

Hariri was born in 1958 in Bonn, Germany, to Iranian expats who had been exiled from their predominantly Muslim homeland for their Baha'i faith. His parents soon moved on to Canada. Says Hariri, "They knew they would always be considered ausländer [foreigners] in Germany."

Hariri chose to follow his father, a structural engineer, into the building trade, but he cites his mother as a formative influence as well. Referring to his mother's sense of taste, Hariri says, "she would rather have one classic dress [or] one excellent, preferably modernist, piece of furniture, than many mediocre ones." He continues to value the judgments of non-architects; for instance, he ran the designs for the Baha'i temple in Santiago past a group of his friends' mothers. (His own mother is bedridden with arthritis.)

The firm's design for the Schulich School of Business at York University won the Governor General's Medal for architecture earlier this year, while a private Toronto residence Hariri Pontarini built was named one of the top 12 new structures in the world by C.C. Sullivan, former editor in chief of the industry bible, Architecture magazine. Designs Hariri drew up for a pair of curvilinear condominium towers in Halifax should utterly transform the city's skyline - that is, if the objections of conservationists can be overcome. (Opponents say the building will interfere with the view to and from Citadel Hill, as well as its proximity to Alexander Keith's Victorian-era brewery.)

Office space: The award-winning interior of consulting firm McKinsey & Company. Courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects.

The materials that have become Hariri's trademark - copper, pale Algonquin limestone, dark woods, huge swaths of glass - were first combined in the Toronto offices of McKinsey & Company, an international consulting firm. It's a long, three-storey building that forms a U around a street-level courtyard. The project was completed in 1999 at a cost of $15.2 million. With its mottled surface and sensitivity to light, limestone seems at once warm and flawed - more human, somehow, than the concrete favoured by past generations of master builders.

A proponent of sketching by hand, Hariri works intuitively, rather than from a set of fixed rules. "I like the accidents that happen when the hand is moving ahead of the mind." A subtle masterwork, the McKinsey building has been a key door-opener for Hariri, leading to further commissions, including the Schulich business school.

In a portfolio of attractive but not exactly revolutionary structures, the $30-million Baha'i House of Worship stands out. The winning design from a field of 185 contenders, Hariri's blueprint will draw in much natural light through a two-layer sheath of shimmering white alabaster and cast-glass. The hillside site will absorb light during the day and emit it at night, like a lantern, framed dramatically by the Andean backdrop.

"I'm Baha'i, too, my parents were persecuted as a result of it, and so you can imagine what this commission means," Hariri says. "Things are unadorned in Baha'i. Music can only be a capella, and no icons can line the walls. So you need to embed a sacred feeling in the building itself."

To reach his lofty goal, Hariri and his team retreated to an artist friend's rustic studio. "We needed to be out of our usual settings to think about this in a fresh way," the architect says. They found inspiration in such diverse objects as Japanese baskets and Scandinavian chairs. At the eleventh hour, Hariri retained an expert in aeronautical software in order to transform the curve-filled drawings and sculptural models into serviceable blueprints.

"It was like falling backwards," Hariri says of the project. "You're not sure where you're going to land, if someone's going to catch you. Anything that came too automatically, too easily, we challenged." It's an apt depiction of the creative process - and a succinct description of Hariri's professional reinvention.